The lost boys of Jaffna

By Andrew Fidel Fernando(Published in 2014)

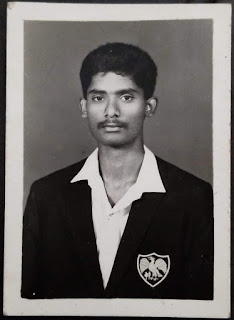

The first time M Kandeepan visited the emigration centre in his city in 1993, the man in combat gear behind the desk asked why he wanted to leave.

"I want to go and play cricket."

"Play cricket where? In Colombo? You want to play for Sri Lanka?"

"Yes, because I am in Sri Lanka."

"You lie. This is Tamil Eelam. You're not going anywhere."

Nineteen-year-old Kandeepan didn't get as far as showing the man his documents. The man had a gun. Men all around him had guns. All over Kandeepan's country, swarms of men patrolled public spaces, wielding fully loaded, ten-rounds-a-second automatic guns.

Kids play on the St.Johns cricket ground in Jaffna

Kandeepan is from Jaffna, Sri Lanka's northern-most urban centre on the western edge of the triangular peninsula that grasps out at India. In the early '80s, Jaffna had been the second-most populous city in the country, but by 1993 it was strung up in the 11th year of a civil war that held the town among its most vaunted prizes. About 70,000 inhabitants remained.

At the time, Jaffna was held by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). They wouldn't grant Kandeepan the permit that would have allowed him to exit areas under their control. He would try another 14 times over the next five months, bringing his father with him to aid in the verbal wrangle, but the most they got in response were screeched threats. They were told that unless they desisted, they would both be shot dead on the spot. It was a crushing experience for the young man with a sky-high dream. A humiliating one for his father, who scrambled on his hands and knees to collect files and papers flung across the floor by boys 35 years his junior.

The LTTE cared little that Jaffna had been a cricketing hub since the late 19th century. They were content to let the city's schools indulge in sport but there would be no leaving the north to pursue cricket as a career.

On that they were forcefully clear. It was the height of the war. If young men fresh out of school would not pick up a gun and a grenade, they sure as hell would not ply their talents for the enemy.

Kandeepan was a Jaffna legend of his time, wildly popular for his ravishing innings and his swagger as he bore down on batsmen with the ball. Yet glory and genius bought him nothing with the LTTE. He was among thousands whose lives hit a dead end at 19, though like others, and the town itself, he refused to give up hope.

During the conflict, northerners paid the highest price for a shot at a better future, for education, for sport, for a tangible escape. Books, bats and medicines were all shipped in - at jacked-up rates - but their own lives were dirt. A drunken soldier, an errant artillery shell, or a single wrong step cut short lives and left families destitute.

When the city was under siege in late 1995, institutions like St Patrick's College in the southern Passaiyoor neighbourhood became a refuge for the infirm. Assembly halls were places of disease and school desks the sites of death. Classrooms were twisted into asylums. The war crushed spirits, scattering a thousand haunting howls in homes and schoolyards across the north. Many of the broken would never be whole again.

Six feet six, dark and lean, 40-year-old Kandeepan now sits upright in a bank manager's office in Jaffna. A pile of stapled papers is squared perfectly to the table edge. His left hand is poised over a red pen, threatening productive action the moment distraction ends. Head shorn and clean-shaven, he is imposing even now, in his executive chair, 21 years after he turned the city's air electric every weekend.

When the city was under siege in late 1995, institutions like St Patrick's College in the southern Passaiyoor neighbourhood became a refuge for the infirm. Assembly halls were places of disease and school desks the sites of death

In the early '90s, Kandeepan played for St John's College, one of Jaffna's oldest institutions. A spired white chapel, reshaped and repainted following the conflict's end, hides a row of tiled classroom buildings. Behind them an old bike shed, still wearing bullet holes, shelled beyond repair, awaits demolition. It was in the large, well-tended field just past it that Kandeepan rose to fame.

When he bestrode the batting crease, and delivered sharp, swinging left-arm pace, thousands packed into Jaffna's small venues to watch.

Kandeepan speaks slowly now, in a firm, taut voice. His eyes lock with his subject's. With a banker's precision for figures, he summons the details of his glory days on the pitch. "In 1992 I scored three centuries, but we played only six matches. My average is actually over 94, because in six matches I scored 542 runs."

At times he wants to force a smile, to be warm, but while his mind dwells on his cricket, his heart won't allow it. "First match itself, I scored 103 not out against Stanley College. Second match I hit 38. Third match against Kokuvil Hindu College, I again scored 105 not out… " And on he goes, counting innings and oppositions. No vacant moments to collect his memory - every run is on the tip of his tongue, every dismissal at the front of his brain.

"Sometimes he did things, people used to just watch with their mouths open," says G Gopikrishna, the long-time St John's scorer, and Kandeepan's schoolmate. "The shots he played and the way he intimidated everyone in the opposition."

Kandeepan's father, SK Mahalingam, had been a popular Jaffna cricketer himself in the 1950s - a quick who modelled himself on the step-by-step pictures in an Alec Bedser pocketbook. In more peaceful times Jaffna's cricket had flourished, and Mahalingam went to Colombo and took his cricket to a junior club level - as far as it would go.

He taught English, a language he speaks beautifully, if with the quaint flourishes favoured by the older generation. "Those bloody Tiger buggers were terrible," he says. "They never allowed him [Kandeepan] a chance. He could have played for Sri Lanka.

Signs of the nightmarish past are everywhere, like this bullet-ridden bike shed next to the playground at St John's. Photo: Hiranya Malwatta

"You know, one time when we went to try and get the pass for him to leave, they offered the pass to me. I said, 'What do you think I can do with this, you bugger? My son is the one that needs the pass.'"

Sri Lanka's cricket is Colombo-centric. Always has been. Every kid who drives past mid-on or pegs back an off stump in a school match hopes to one day do the same in one of the grounds in leafy Cinnamon Gardens. If Kandeepan could not go to Colombo, he knew the runs that had flowed from his bat and the scalps he had piled up in a heap would count for nothing.

After his 15th dispiriting trip to Jaffna's emigration centre, he was all set to give up on cricket and find a job. But in 1995 a benefactor who had watched Kandeepan play devised a tricky route out of the north. He arranged an entry-level bank job for him in Nuwara Eliya, deep in the central hill-country. It wasn't a spot in a Colombo club, but it promised some sort of future.

"Even getting that was not easy," Kandeepan says. "To let me go, I had to give my neighbours' names as a bond, so if I didn't come back to the LTTE area in time, those people would be put into the LTTE bunkers. Then only, finally, they allowed me."

Leaving the north was its own bloodcurdling challenge. Jaffna residents with a permit would board a bus that took them as far as the edge of the peninsula - a two-hour journey; longer if the roads were bad. The only overland crossing to the mainland was at the Elephant Pass isthmus - the war's most constant theatre of violence. Way out of bounds for civilians.

So travellers would instead board banana boats, always under cover of darkness, to hide from navy officers who might mistake them for LTTE personnel. Around midnight, they would reach the shore near the town of Pooneryn, pile into a tractor and traverse marsh and mud toward the major inland arteries. In a village near the LTTE administrative capital of Kilinochchi, they would disembark, pay the fare, and hire bicycles to ride into town. Another bus would transport travellers to the last LTTE checkpoint, near the town of Vavuniya, where the journey's terror spiked to a climax.

If the LTTE men were happy with your papers, you walked along a raised pathway, half a metre wide, across a mile of no-man's land. Either side of this sliver of safety were landmines, packed in like plantation pineapples. If shooting suddenly began across the divide, paralysed in position, you were as good as dead.

"When I was crossing, there were a lot of people," Kandeepan says. "Sometimes the path would get muddy and slippery. Someone far behind me fell into the mines. He was an old man. He lost his legs. No one could help him."

In 2014 Kandeepan was 40. Now 46, Kandeepan is desk-bound, but he makes sure talented young cricketers who come his way in Jaffna don't end up like him. Photo: Hiranya Malwatta

Travelling to Jaffna on the A9 in 2014, it seems a wonder anyone could wish to leave the peninsula. With long, verdant fields of paddy and lush thickets of brush, much of the landscape is unmistakably Sri Lankan, yet it is spiked with a distinctive northern energy. Palmyrahs dominate the horizon, with long, thin trunks that rise straight, then burst into a sphere of palm branches, 20 metres in the air.

The town wears heavy scars of violence, yet it is not marred by the dilapidation. At the heart of the city, the Nallur kovil sends up its ornate sculptures in the narrowing, burnt-orange gopura. In the motley corner stores, the inexplicably abundant '60s roadsters, and the rich, blazing crab curries, Jaffna's pull is restrained but powerful. The land itself is a patchwork of dense greenery and shallow saltwater inlets. When the tide is in, shimmering turquoise waters curl around the peninsula. At sunset, painted storks wade around in single file, beaks dipped in water, while egrets in flight skim the surface around them. How could this place have been the scene of such brutality? It's hard to reconcile mines and mortars with such soul-soothing bliss.

Almost 400 kilometres south of Jaffna, Kandeepan had renewed hopes for cricket when he arrived in Nuwara Eliya. He knew he could not risk losing the job that his friends and family had moved mountains for, but he could make it to matches in Colombo on the weekend and be back by Monday morning for work, he thought. That plan quickly unravelled.

Nuwara Eliya was no war zone the way Jaffna had been, but to be a young Tamil in the south was to be universally suspected and routinely harassed. A man from Jaffna with a name like Kandeepan could be anyone. Was he a Tiger on a reconnaissance mission? A courier for the LTTE? Or worst of all, a Black Tiger? Long before Al Qaeda and Hamas, the LTTE had pioneered the suicide bomb. An elite unit of cadres served the cause in a skein of bloody eruptions, leaving an agonising gash on the national psyche.

There were at least a dozen police or military checkpoints between Nuwara Eliya and Colombo. On any single trip, Kandeepan could have been detained at three or four of those until the forces ascertained he was not a threat. If he was unlucky, he might have encountered a particularly vengeful unit, been thrown in remand, or beaten. During the 26 years of war, thousands of young men on innocuous errands and mundane journeys vanished forever.

So Kandeepan put his head down. He let his dream sink and worked hard. He rose in the ranks until he could request a transfer back to his home town. Eighteen years later, it had become a safe place again.

Caged in this air-conditioned room, tethered to his desk, Kandeepan has watched himself become a suit when he should have been on a pitch, on the back foot, hooking. He sometimes hears echoes of "Kandi, Kandi" ringing in his ears; recalls when kids around town sneaked glances in his direction and whispered to each other, smiling.

"That's Kandi."

"I know."

Now people call him "Sir". He provides for a young family and does right by his parents. "But I'm realising I have the wrong job," he says. "Sometimes I wonder what I am doing here." It is disarming to hear a man of such sturdy self-possession make himself so vulnerable. "Being a bank manager is very difficult."

A maintenance engine rides on a newly built track over Elephant Pass © Hiranya Malwatta

If he has an hour to spare at lunchtime, he is on the field at St John's, imparting what he knows to the youngsters coming through. When a promising Jaffna cricketer began working in his branch in 2013, he immediately appealed for the young man to be transferred to Colombo.

"What happened to me should not happen to them. They have a chance," Kandeepan says. His eyes are filled with regret.

In Colombo, the likes of Rangana Herath and Nuwan Kulasekara scan through street-side markets with smiles acknowledging their celebrity. Only on occasion do fans approach with a camera phone. Jaffna is not given to such civil inhibition. Through the tormented '90s, cricket was the city's escape from fear and pain. Fighting in the town would force months-long evacuations, and when families returned, their homes were often shot up and ransacked, landmines planted where flowerpots had been.

To watch a curling outswinger or a crisp cover drive was to suspend reality, to achieve temporary nirvana, and every week thousands clamoured to lose themselves in cricket. When they returned home in the evening, their walls would still be dressed in bullet wounds. Their children would be studying on light stomachs, by candlelight. But to watch a match in the flesh was to lighten their burden. So they made heroes out of teenaged talents. Homes would be open to them, drinks and meals free.

When Kandeepan settled for this life, away from cricket and Jaffna, the town he ruled found someone new. It was inevitable. His place in the public imagination was taken by AS Nishanthan, a wicketkeeper-batsman from St Patrick's whose movements behind the stumps were as sure and comely as his flourishes with the blade. Nishanthan had met Kandeepan on the field once, in one of the biggest clashes of 1993. It was his second match for the senior team at 15 and Nishanthan remembers the game well.

"At that time, Kandeepan was like a giant. Everyone knew he was the key," he says, stashing away a smile and arching his eyebrows. Twenty-one years later, he is still in awe. "I remember one of the St Patrick's old boys came and told us, 'Kandeepan likes to hook, so why don't you get him to play the hook and get him caught at the boundary?' All everyone could talk about before that game was Kandeepan, Kandeepan, Kandeepan. How to get him out?"

St John's batted first on St Patrick's home turf. It is a small venue but a pretty one, with classrooms skirting the edge, and the gold-tinged tower of St Patrick's Cathedral peering out above the tiled roofs. Within half an hour of the start of play, about 4000 bodies jostled for a view at the ground's periphery. When Kandeepan arrived at the crease at 14 for 2, St Patrick's set the trap. Fine leg and square leg were pushed out to the boundary. The bowlers prepared to feed his most elemental cricketing impulse.

"The first bouncer went for six," Nishanthan says, "but we didn't stop trying because we knew he would keep playing that shot."

The next ball was another bouncer, faster and fiercer, Nishanthan says, and the bowler's bravery was matched by another hook. Only, this time the batsman erred. The ball took the splice and flew high. Fine leg moved beneath it. A tumescent hush hung in the air.

"It should have been an easy catch but the fielder dropped it," Nishanthan says. "I thought that was the game." The whooping St John's supporters drowned out the groans from the home fans. "Kandeepan doesn't just give chances like that. When he gets a chance, he scores a hundred, and when he scores a hundred, it's not like 100 or 105 or anything like that. He gets 150 or 170. Not only me, everyone thought that. He had been hitting a lot of runs in the weeks before." Nishanthan's side got lucky. A few minutes later, a full-length ball stopped on the matting and forced Kandeepan to drive at it early. Short cover held firm this time. He was gone for 21.

The smiling PT teacher: Nishanthan batted like he was in a trance, and kept wicket for St Patrick's, who he now coaches. Photo: Thusith Wijedoru

But though they muted him in one discipline, St Patrick's couldn't survive Kandeepan with the ball. Defending a small score, he took eight wickets in the first innings, then four in the next, firing the thrusters beneath an explosive St John's victory.

Having arrived at No. 8 in the second innings, Nishanthan glanced Kandeepan for four early in his knock before sending him through the covers on his way to 18 not out. It would be enough to protect his place in the team for another week. More than that, Nishanthan had resisted Kandeepan in imperious form. He knew he belonged.

Nishanthan's rise was more gradual than Kandeepan's. He is shorter than the older man, and a little rounder, at 37. His easy white smile is set off by striking hazel eyes. A faded striped shirt is tucked into black trousers over a slightly bulging belly. He does not command a room like Kandeepan, nor move with quite the same intensity of purpose. But there is a generosity of spirit about him, and an approachable air that he has perhaps groomed over a 15-year career as a coach and PT teacher.

Nishanthan is too retiring to talk himself up. But almost all who saw him play are adamant he was singularly sharp behind the stumps, and phenomenally difficult to remove when set at the crease. He excelled in the lower age groups, before graduating to Under-19 cricket at 15. Eventually, his peers say, Nishanthan would have pushed for a place in the national team; only, he was bred in the wrong corner of the island.

Nishanthan was a disciple of timing and touch, a veritable artist with the bat by every recollection, but it was not his wrists or fleetness of foot that fed his legend. Swashbucklers were as adored in Jaffna as anywhere else, but far beyond the cricket field, the city bore a history of deep delight for the cerebral.

There are few better examples than the tale of Jaffna's library. When it was established in 1933, it was little more than a depository for several private collections, but in fewer than 50 years of ardent academic affection, it had grown into one of Asia's most precious intellectual resources. A trove of palm-leaf manuscripts, centuries-old music and poetry, philosophical jaunts, historic documentation, and with a gorgeous, gleaming Indo-Saracenic dome: the very pride of the town itself.

There is some debate over who set the goon squads loose on the night of June 1, 1981, though many historians contend the nation's government ordered that evening's atrocities. What is beyond dispute is that the burning of the Jaffna library is among the most abhorrent modern acts of biblioclasm. Almost 97,000 titles, many among them priceless not only to Tamils but to Sri Lankans of every race and creed, were sent up in flames. Jaffna's people felt the soul of their city had turned to ashes. Tragically and predictably, the sacking provoked a response so fervid it would lurch Sri Lanka closer to its civil war.

In the motley corner stores, the inexplicably abundant '60s roadsters, and its rich, blazing crab curries, Jaffna's pull is restrained but powerful

Jaffna's passion for pleasures of the mind spilled over onto the cricket field, and it was here that Nishanthan set himself apart. At the crease he would slip into a state of mind known in the local tongue as nidanam(நிதானம்). In simple Tamil, it means focus, but in the milieu of Jaffna batsmanship, the term comes charged with much more. Nidanam is the art of being impervious to distraction, of being ruled by tranquillity through all duress. It is not quite the clear head so valued in modern cricket - more a burning, single-minded purpose. Kumar Sangakkara is another with nidanam, it is said. That is foremost among the reasons why his method is adored as much by Jaffna coaches as by the young northern boys growing up watching him on their screens.

A Nishanthan innings, born of nidanam, was a daydream; a swirling veena melody over a rolling tabla pulse. Kandeepan's crowds had throbbed to his heady adventure, but when the old hero moved on, the city's new darling dealt in contentment. By the time Nishanthan struck a ton against St John's in 1995, as the St Patrick's vice-captain, every kid on Jaffna's streets knew his name.

"It wasn't just the boys from my own school, even the supporters from other schools would come to watch us play. Sometimes very old gentlemen would come before a match and say, 'Nishanthan, tomorrow's match is against Central College, no? Don't just get 50 runs, play slow and score 100 runs, ah.' If you did well, after the match they would come and give 50 rupees, 100 rupees - like that."

For all the love and praise Kandeepan and Nishanthan drank in, there were no delusions about their place in the world. Even on the field, the worn matting strips and their disintegrating equipment anchored them to reality. Repeated requests for new gear would only be heeded if the school's headmaster could find several other schools willing to go in together so they could buy in bulk and save on shipping. When the gear eventually arrived in Jaffna, it cost twice, sometimes three times, what it did in Colombo.

"We had one batsman who was a big hitter," Nishanthan says in his lilting Tamil accent. "He really hit the ball very far. Out of the ground - like that. After one match where he had three sixes, our coach was very angry at him. 'Why you are hitting the ball so hard,' our coach was asking. 'If you just hit it over the boundary line it is still six. You don't get extra runs if the ball goes to India. Why are you trying to break our bat?'"

That year, 1995, which should have been Nishanthan's penultimate one in the school team, turned out to be his last. "I would have been captain in 1996," he says. "But before the next year, the army came. Riviresa took place and we all had to leave."

Riviresa, Sinhala for "sunbeam", was among the Sri Lankan armed forces' most successful operations in the civil war. The LTTE had occupied Jaffna since 1989. Following the breakdown of a round of peace talks, the government forces moved into the northern edge of the peninsula in October 1995. They pushed southwest, winning decisive battles and striking down a volley of counterattacks. By late November they bore down hard on the city itself from three directions. Realising the futility of their position, the LTTE fled Jaffna in the dead of night, early in December.

When the Sri Lankan forces took the city, its inhabitants had long since emptied into a north-western pocket of the peninsula that had remained relatively unaffected by the operation. Armies stretching back to antiquity had warred over Jaffna, so anticipating violence was hardwired into the town's DNA. In their seven-month displacement, the people resolved to soldier on, assembling makeshift classrooms beneath coconut trees and improvising a loose micro-economy held together by barter.

The turf pitch at St Patrick's. Photo: Thusith Wijedoru

The 1996 World Cup was viewed in exile, on beaten-up television sets powered by repurposed car batteries. Amid the cadjan huts and tin shanties, the tournament was followed with such intensity that fights broke out after Sri Lanka's semi-final. "When Sri Lanka play India, it is like a war here," says a local.

Cricket is Sri Lanka's most pervasive passion, yet it's oddly poetic that it also serves as a forceful symptom of the nation's divisions. In the decades following independence, Tamils across the country had felt their language and culture had increasingly become marginalised as Sinhala nationalism gripped the political apparatus in the south. For about half of Jaffna's population, this drove deep, defining a wedge between themselves and everything Sri Lankan, including the cricket team.

For many it hardly mattered that Muttiah Muralitharan was becoming Sri Lanka's greatest player. Murali's family emigrated from southern India in the 20th century. His Tamil smacks of the modern Chennai vernacular, while Jaffna is proudly among the most vibrant bastions of classical Tamil. For all the humanitarian work he has since done in the north, Murali's experience is not viewed as typical of that of the Tamils who have lived, loved, bled and died on the island for millennia.

Even now, on match days, the town sometimes lapses into communal squabbling. Those who have aligned themselves with Tamil Nadu clash with the Sri Lanka fans, but perhaps this violence is about to retire into the history books as well. The rising generation in a unified Sri Lanka unequivocally favours the darker shade of blue.

In mid-1996 Jaffna was cleared for re-inhabitation, and families returned to a gutted town, forced to begin again, almost from scratch. What remained of the community's resources was used up in the effort to reclaim homes, schools and businesses. Nishanthan had dreamt this would be his year of glory, but instead it was among the most gruelling of his life. His ambition was shot to ribbons in the scramble to survive.

After finishing school, Nishanthan attended university in Jaffna in the late '90s and took a job at his alma mater soon after graduation. Quickly he was put in charge of the school team. It had been a difficult assignment to begin with, as the war whirled through the north. There were three years of respite when a ceasefire was set down from 2002 to 2005 and the government and the LTTE sought to end hostilities over a negotiating table. But like the eye of a cyclone, that tenuous peace passed, giving way to a fresh blur of blood and bombings. The final hellish vortex in 2009 will haunt the island for decades.

In the time that followed the war's end, Nishanthan's reality would change. Within months, top national cricketers had made trips to Jaffna, and in the years since, resources have flooded in from the south, as Sri Lanka's cricket community embraced their northern brothers. Nishanthan's team at St Patrick's has many more than three bats, thanks to initiatives like the Mahela Foundation - Jayawardene's charity, which provides cricket gear to less privileged schools and clubs. When Sanath Jayasuriya visited Jaffna in early 2013, he set in motion a project that led to a turf pitch being installed at St Patrick's. As the only surface of its kind in the province, it has become a training resource for teams from all over the north.

"It's a great thing for us, because now our boys have some idea how to play when they go to play teams from the south, on the turf pitches," Nishanthan says. "Otherwise they really are not sure about how to play spin. They struggle."

Girls play a cricket match at a ground overlooking the Jaffna library. Photo: Hiranya Malwatta

Nishanthan's renown for skill and care in his coaching was among the reasons St Patrick's was preferred for the turf square. He is also a junior national selector, under Jayasuriya, part of the panel that picks age-group teams for Sri Lanka. Nishanthan counts Jayawardene among his admirers. Jaffna has far to go before its schools can match the southern colleges' resources, but the bats in Nishanthan's care rarely break before they are well worn. The pads and gloves go further on his watch.

"I come from a different time," Nishanthan says. "It's like a different world, actually." He laughs. When he speaks of what he hopes is ahead for Jaffna cricket, he rarely ceases to grin. His days are spent in the open air, bowlers pounding in from behind as he studies batsmen lunging forward and flicking to leg at the opposite end of the net.

"These boys don't have excuses," he says. "If we start beating better teams, then only we will get better facilities. Nothing like before anymore. We have the control, you know? Nothing like before."

Courtesy: thecricketmonthly.com

தொடர்பான கட்டுரைகள்

1. இரு யாழ் பெண் கவிஞரின் கொலைகள்

Comments

Post a Comment